In sydney, a new economics recognises its existence

SOMETHING SIGNIFICANT happened on Thursday 27 September 2012. How it unfolds over the next few years will determine whether it will be a good idea stillborn or the start of an authentically new economy.

I’m talking about Australia’s first collaborative consumption gathering that brought together, at the Australian Technology Park in Redfern, people engaged in this new economics. It was a gathering of those who are interested and ready to taste the water—small business start-ups—both not-for-profit social enterprise and for-profit small business entities venturing into the new economic territory—and a few from local government. The City of Sydney, Parramatta Council and Randwick City Council’s sustainability educator—who has already rum workshops on the topic with Annette Loudon from Sydney LETS—were present. It is these people who have the opportunity to facilitate a prosperous future for this new industry.

An aside about terms. There’s an alternative term for collaborative consumption that I prefer—collaborative economies. That’s what Randwick City Council’s sustainability educator calls it. I like it because the term ‘consumption’ has acquired overtones of excess, waste, environmental and social destruction and resource depletion and has gained something of a bad name. I like it also because the term ‘consumer’ is one derived from the wooly world of economists and catagorises people as dependents, ignoring the reality that they are often producers as well as consumers.

Rachel’s ideas

The keynote speaker at this first gathering of the collaborative economy clade was Rachel Botsman, the Sydney woman whose research into the phenomenon was published as the book, What’s Yours is Mine (2010; Harper Collins, USA), a few years ago.

Rachael didn’t invent collaborative consumption but she did describe it and in so doing demonstrates a curious phenomenon driven largely by the way mainstream media works.

We can call it the ‘TED Talks’ or the ‘authorship’ syndrome. It works like this. Someone writes a book or does a TED Talk and the media then positions them as an authority on it even though they did not invent it. This has emerged as a critique of TED Talks, the popular, presentation format exposition of new ideas that you can find online.

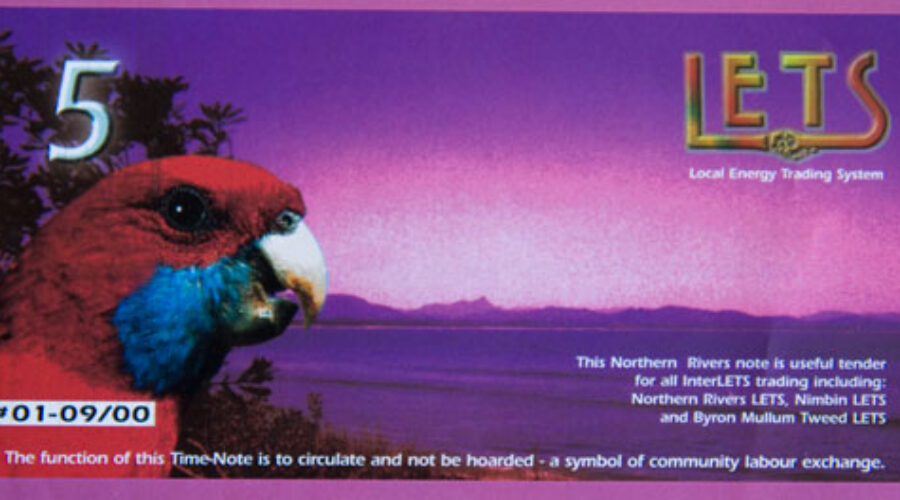

Collaborative consumption—as far as I can work it out—goes way back in Australia to the early 1990s and the emergence of the peer-to-peer Local Exchange and Trading Systems—LETS. That was the time when LETS inventor, the Canadian, Michael Linton, worked out of Randwick Community Centre. It was around that time that we set up in Sydney southside something called Worknet—a small scale, time-based mutual assistance scheme to help people repopulate their backyards with edible plants. Unbeknown to those later creating it, Permablitz was essentially a reinvention of Worknet but it came at a time when people were ready for it and so it spread nationally.

Rachel Botman’s book was the first to describe and categorise the current manifestation of the peer-to-peer and small business-based enterprises that make up what has been labelled collaborative consumption, whose business model is to facilitate sharing rather than buying. She made sense of what was going on and in doing so acquired a deep knowledge of it.

Technology-enabled trading

Collaborative consumption, the name given to the phenomenon of business and community enterprise based on sharing rather than owning stuff, is a child of Web 2.0—the collaborative or read-write web. It is a technology-enabled phenomenon that would not have experienced rapid growth without the interactive online services and software we now use.

That—the availability of the technologies of the worldwide web and the mobile internet—is why we are seeing collaborative consumption blossom now rather than demonstrating a direct lineage with its first popular manifestation in Australia as LETS—Local Exchange and Trading Systems.

A bag of models

Collaborative consumption initiatives often take the form of social enterprise of the not-for-profit type or, in some manifestations, as for-profit ‘social businesses’.

The Grameen Bank in Bangladesh, set up by Muhammad Yunus, then Head of the Rural Economics Program at the University of Chittagong, has been the model for social business. He established the Grameen bank to end rural poverty.

Both for and not-for-profit models of collaborative enterprises are set up to satisfy some socially-valuable purpose—it’s social need that often triggers the creation of the enterprise, as Nic Frances describes in his 2008 book, The End of Charity—time for Social Enterprise (Allen & Unwin, Sydney). Sydney Food Connect—the community-supported-agriculture social enterprise—GoGet carshare and food co-ops are a few examples but there are numerous others.

Let’s be clear here. Social enterprise, not-for-profits, sometimes rely on grants and charity, however many operate as small businesses. The difference is that they are often governed by a management team or board of directors, and what in conventional business would be called profit is known in social enterprise as ‘operating surplus’. Rather than going to the company’s principles or to shareholders, it is invested in the social enterprise. Co-operatives work in much the same way.

There are also the peer-to-peer service systems of the voluntary community sector such as LETS mentioned above, the popular Permablitz model of mutual assistance for home garden construction and the community-based goods exchange and reuse service, Freecycle.

Rachel says that there is a “massive” difference between the for-profit and not-for-profit models. She favours for-profit and sees systems based on points or time (such as LETS) as having to deal with the barrier of educating people about how to use them. Given their past popularity, I’m not sure that is all that large a problem.

There are clearly efficiencies to the business-based models, however for those interested in community development and building the capacity of communities they can be seen to offer less opportunity for community self-help because, with the exception of some peer-to-peer models, they offer less direct participation in management.

Business-based models of collaborative consumption could be seen as positioning people in the community within the usual business context, as customers rather than as doers. While the business model, whether not-for-profit or for-profit, has the potential to place collaborative economic enterprises on a firmer footing and provide greater potential for longevity than those based in the voluntary community sector, it encapsulates participants within the small business milieu that many may see as no different from any other type of business and calls upon an entrepreneurial approach that is not always available, even though LETS called on a socially entrepreneurial mindset which has many similarities to that found in business.

It’s good that this all of this happening, of course, because it goes a little way to reinventing the economic system as capitalism-at-a-human-scale rather than the predatory, global capitalism currently doing its best to discredit the system.

A cascade of ideas

As people threw questions to Rachel, a cascade of learning and ideas flowed:

- asked to rank Australia on the global uptake of collaborative consumption, she placed it fourth after, in order of uptake, the USA, Europe and South Korea; she did say that Australia should be leading, with Sydney the collaborative consumption epicentre of the world

- as to competing with the likely expansion into Australia of overseas collaborative consumption businesses, which Rachael sees as inevitable, developing a strong point of difference to what they offer and embedding local businesses in communities would strengthen their position in the face of experienced businesses with a lot of know-how

- the question of critical mass is important, Rachael explained; what constitutes critical mass would differ with some models likely to work better in the more densely populated urbanised areas while some, such as ride-sharing, are likely to do well where long distances are involved

- the curation of quality when an enterprise is young is important to building reputation and a community base—reputation and its fellow traveller, trust, are the basis of collaborative economies; presumably, this would help in competing with overseas collaborative consumption enterprises entering the Australian market

- the user community plays an important role and should be cultivated and curated as an organisational asset

- some people are surprised to learn that there is a company involved in some peer-to-peer operations while in others, like transport service provider GoGet, the company has a high visibility as the mediator of the service

- collaborative consumption is a form of reputation economy and there is a need to establish standards for reputation and trustworthiness across the range of enterprises; some, like the peer-to-peer accommodation service, AirB&B and Couchsurfing, rely on user recommendations; the idea of a portable, verifiable ID for those offering services was raised (perhaps the new ‘endorsement’ feature on the professional social network, Linkedin, in which members can endorse the work of others, is a start to this); the notion of reputation is related to a reality that wasn’t mentioned at the gathering but that certainly exists—that in an age of Web 2.0, companies have effectively lost control of the way the public perceives them—they are more or less what people say they are online

- people entering the collaborative consumption market in any form would do well to decide where on the spectrum, from for-profit, social enterprise, peer-to-peer and voluntary community-based systems they will operate; they should then focus on that

- Rachael said they she anticipates cooperation between enterprises

- collaborative consumption has evolved as a decentralised marketplace, according to Rachael, but you can see monopolies coming up here and there; this is a reason for niche enterprises to develop a strongly defined point of difference to other enterprises; as they grow, enterprises need to retain the benefits they offered while small.

Collaborative consumption—local economy or global?

Just a week before attending the Collaborative Consumption gathering I attended the seminar at UTS with US attorney, economist and consultant on the development of local economies, Michael Schuman. Michael, a Fellow to the Business Alliance for Local Living Economies, has done a great deal of research on economic localism (which I prefer to call ‘regionalism’) and is author of several books on the topic.

When Rachel mentioned the likely intrusion of foreign business working in the collaborative economy into this country, Michael’s comments on the economic and social value created in an area by locally-owned business came to mind. I recall Michael saying that the growing phenomenon of crowdfunding was good in principle but usually did little to benefit local economies. Could this become the same with that other good idea—collaborative consumption—if it becomes part of the global economy?

While there may be tensions between collaborative consumption and economic localism, there’s a lot of buzz around collaborative consumption at the moment and it is being promoted by influential people who are often economically and politically astute, many with tendrils in the voluntary community sector of society. Were they to witness Australian or more local enterprises being displaced or disadvantaged by foreign operations, and were they to make the connection to the effect of this on local economies, what you might see is a wedge driven between the business end of collaborative economy and the voluntary community and social enterprise side.

This would be unfortunate and applying Rachel’s idea of businesses curating the quality of their goods or services and developing strong points of difference could play a tactical role in retaining a dominance for Australian enterprises in this country. Perhaps being locally-owned and based could be one of those strongly-emphasised points of difference.

New role for local government

Both Randwick City Council and City of Sydney have already offered community workshops in collaborative consumption and Sydney’s Waverley Council is believed to be the first to support the popular garage sales trail.

This demonstrates the new roles local government is being expected to take. We’re far from the days when councils dealt only in the prosaic services of roads, rates and rubbish and it’s an indicator of how community expectations of local government are changing. Councils leading in this work are hiring staff—still far too few of them—who think well beyond the narrow, established confines of traditional council business to push the edges in a way more to do with a role not as conventional public servants but as civic entrepreneurs who assists communities make things happen.

It’s the business of councils to look for ways to improve their local economy and, as the City of Sydney’s Tom Belsham told the gathering, that is his council’s interest in supporting collaborative consumption.

New days, early days

Collaborative consumption is a new phenomenon still in its early days. It is at the start of its evolution and its future depends largely on how those active in it portray themselves to the public.

There is in this country, especially among some ‘green’ groups, a distrust of business whatever its scale. This was pointed out to me years ago by the Sydney man who invented the social investment or ethical investment industry here‚ Damien Lynch. This, Damien said, is a barrier to enterprises offering social value.

And that’s what collaborative consumption will have to offer as its core product—social value—both to participants and to communities.

Tom

October 28, 2012 at 11:13 pmHi Russ,

Great post and thanks for reporting on the event. As an attendee, I was really excited by the breadth of companies and the different industry sectors collaborative consumption organisations can potentially disrupt – car sharing, food, tourism, hotels, and (my company PetHomeStay’s focus) pet care. I have also put a post on our PetHomeStay blog that summarised some of the main questions :

http://pethomestay.wordpress.com/2012/09/29/rachel-botsman-qa-collaborative-consumption-part-2/

thanks

Tom