Movie of a troubled life

IT WAS WHEN I was living in Byron Bay, and when in earlier times I would stay at the community atop the rainforest escarpment above Broken Head where my partner lived among the carpet pythons, the brown tree snakes and the green frogs that I would walk that stretch of coast that spans south of the Head so that I could partake of its rocks protruding above the white crashing surf and its yellow beaches scalloped between forest-clad headlands of dark green.

It offered a ruggedness with rainforest cascading down the escarpment to meet the sea in a confusion of rock and sand, and it offered a still, humid world within that forest of palms and ferns and trees unknown and little scurrying sounds in the undergrowth. It took awhile to realise why this coast reminded me of something. Then I realised.

Sure, Broken Head wasn’t Big Sur. In comparison, it was just a microcosm of it, grand in a more subtle way, and there was no one like Jack Kerouac living there in a shack (though the residents of the community lived in shacks around the big community house), only sometime environmental campaigner/state MP/surfer Ian Cohen at home in Serendipity, his rainforest-wrapped and mosquito-infested home, and veteran surfing movie producer George Greenough further along the escarpement in his pyramidal house sticking up above the rainforest.

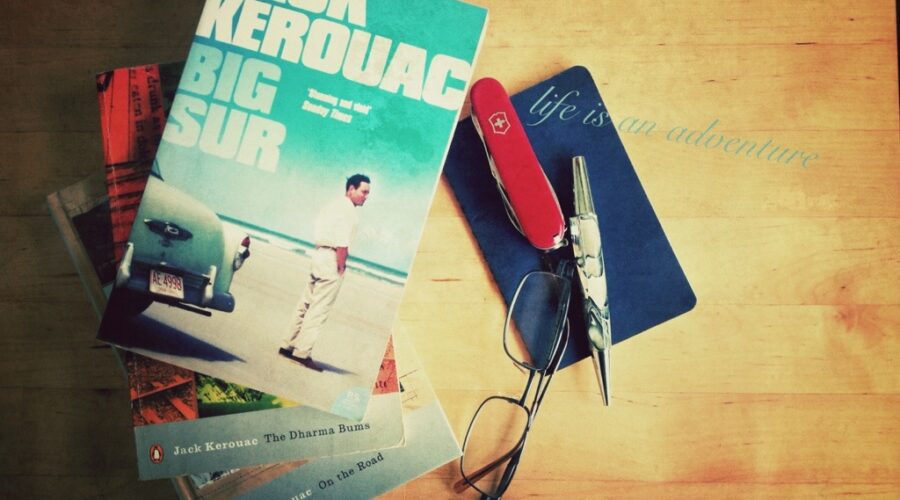

Big Sur. Twice, maybe three times, I’ve read the book and last night I watched the movie. The book — it must have been in the 1970s or the following decade that I first read it — forms the sad final volume of my three favourite Kerouac novels that started, chronologically, with my favourite, The Dhamma Bums, then the discovery of On The Road leading to Big Sur by way on Lonesome Traveller and Desolation Angels.

It was last year, I think it must have been, that I watched a recent movie of On The Road, Kerouac’s seminal book that documented in fictional form his journeys across the US, New York to San Francisco, that he made in 1947 and that was published a decade later. I enjoyed that and, having read that book three times over the years since discovering it as the right time of my life in the late 1960s but more likely the 1970s, I found the movie a little lacking in some quality that, not having any of the mental tools of film criticism, I can’t quite define. It was ok in its generality as a story, but it was clearly an adaptation of something literary that was far better.

I usually find films based on books bear only a superficial resemblance to their paper counterparts. But Big Sur the movie was different. There’s much narration straight from the book and I found that the film parallels the book quite closely. The visual portrayal of Bixby Canyon where Kerouac sought escape in 1960 from the attention that the success of On The Road brought truly portrays the forest and the rugged Big Sur coast, the trail to the cabin through the bush and the highway where it crosses the canyon on that high, elegantly-arched bridge.

…there’s my hopeful rucksack all neatly packed with everything necessary to live in the woods, even unto the minutest first aid kit and diet details and even a neat little sewing kit cleverly reinforced by my good mother (like extra safety pins, buttons, special sewing needles, little aluminum scissors)…

Seeking refuge from attention, Kerouac journeys to the West Coast and after a binge drinking session with his Beats friends in San Francisco he makes it to Bixby Canyon, to the shack of his friend, the Beat poet Lawrence Ferlinghetti. Here, he writes reflectively and comments on the popular perception of himself and contrasts that to the reality…

…all over America high school and college kids thinking “Jack Duluoz is 26 years old and on the road all the time hitch hiking” while there I am almost 40 years old, bored and jaded…

That first stay was one of three periods spent in the shack, the others often in company of his Beat friends from the city. But here, alone, you get the picture of how Kerouac struggled with life… he had wanted to escape the city and popularity, but once at the shack he pines for the city and his friends…

…and it’s finally only in the woods you get that nostalgia for cities at last…

And so it goes… canyon to city to binge drinking… city to forest and stream… until, leading to a transition point in the film, he has a delirium breakdown, falls asleep and awakes seemingly a changed man whereupon he realises he must once again make that transcontinental journey back to his mothers’s home in New York. Transition, both downwards and upwards and from city to shack runs as a theme in the film as it ran through this period of Kerouac’s life.

When I was living in a little shack myself, alternately freezing through the winters and baking through the summers in the uninsulated little building among the fruit trees and chooks in a backyard in Manly, I would visit a second-hand bookshop in town that featured a rack of titles by the Beats. Once, I asked the young woman behind the counter at Desire Books who bought these titles and she told me that young people were starting to read the stuff. I found that interesting… could it be, I asked myself, that they are discovering Kerouac just as I had done at a similar time of life? I hoped so.

Associated writing…

On Jack Kerouac, Hemingway and a Literary Friend: http://pacific-edge.info/2007/07/on-kerouac-hemingway-and-a-literary-friend/

A Remarkable Book and a Remarkable Person: http://pacific-edge.info/2011/04/kingscross/

Peter Matthiessen, writer – farewell & thanks: http://pacific-edge.info/2014/05/peter-matthiessen-writer-farewell-thanks/