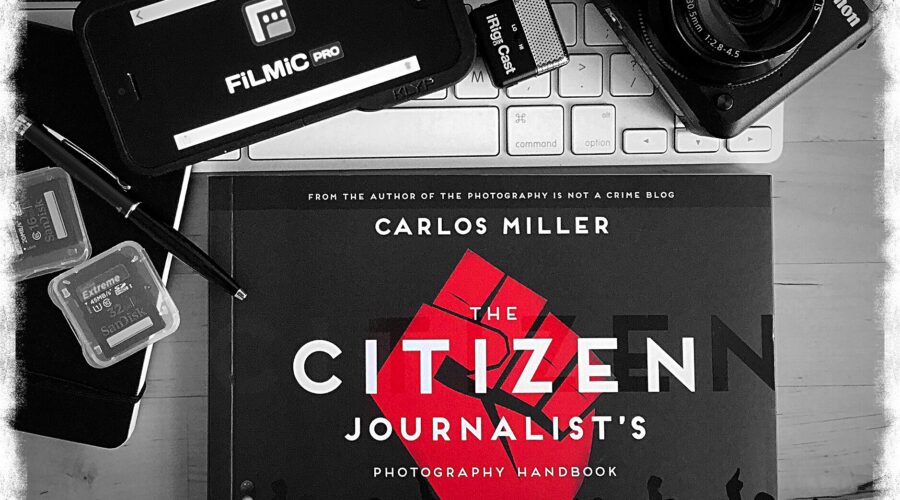

The citizen photojournalist: here’s the manual

WHO BETTER than a multimedia photojournalist and blogger whose work has also been picked up by old media’s newspapers and TV to write a book on citizen journalism? After all, Carlos Miller has pioneered this new field of independent journalism and popularised it in his blog, Photography Is Not A Crime.

Carlos’ book brings together all that a citizen journalist needs to know, though from a US perspective which can be quite different in its legals to what we have in Australia. Despite that, his book stands as both an introduction and a guide to the practice. And here I agree with Carlos — a better term for that practice is ‘independent journalism’ — however he explains that he uses the ‘citizen journalism’ label in his book because it has become the common term.

Accompanied by profiles of citizen journalists, the book’s 160 pages ranges through the history of the practice; the case for it and the case against and why that is wrong; its photographic tools including the ubiquitous smartphones; video and DSLR cameras; social media platforms and how to use them; legals (as apply in the US — have to do your own research for those applying in Australia); and examples from around the world where citizen journalism has proven of use in globalising the local, such as the Arab Spring, Occupy Wall Street and more.

Going multiformat a necessity

Carlos’ book is oriented to the citizen photo and video journalist rather than to the writer. Yet, when I did a course in photojournalism in the days when we filled our cameras with film rather than SD cards, the course instructor told me how fortunate I was that I could do both photography and writing. In saying that he couldn’t know that this multi-platform ability would become basic to the practice of journalism in general and to citizen journalism in particular. Now, to practice in this field, it helps to be able to combine still photographs with video and words.

If you are an aspiring citizen journalist, following-up Carlos’ book with a little learning on basic news and feature writing would round out your skills. Despite the saying about a picture being worth a thousand words (was some photojournalist of photo editor at a newspaper behind this?), those words I mention are often necessary to place the images in some kind of context and, so, to give them meaning and link them to related events.

How to practice

The Citizen Journalist focuses much on covering campaigns like Occupy Wall Street, however citizen journalism is more than this and includes what we know as documentary photography and street photography. Once, I used to cover street actions like those in the images in the book and that in itself is its own little field of practice with its images falling into the documentary category.

That other category, street photography, is also a type of documentary photography that documents, for the historic record, our changing cities and the people who inhabit them. To look back on old photographs of city locations and compare them to contemporary images taken from the same location can bring home just how our cities change dramatically. Without documentary and street photography we lose our collective memory.

Carlos’ book is useful for these types of citizen journalism, however if you want to explore street photography as a type of citizen journalism combining photography and text I recommend supplementing Carlo’s book with one specifically on street photography, as there is much to learn about how you approach that.

Validating the practice

I was just about to write that Carlos’s book helps to validate the practice of citizen journalism but I realised that it has already been validated, especially due to its role in significant events like the Arab Spring and the citizen uprising in Turkey.

There has been a tendency for some professional journalists (those paid for their work, that is) to belittle citizen journalism as lacking rigour, journalism ethics and practices. Some of this can be put down to professional jealousy towards a new type of journalism, some to changes in the media landscape that has seen the closure of established old media and the loss of jobs in journalism, and some to journalists lacking skill in combining text and images.

Some of their criticisms are correct and I believe that citizen journalists would do well for their credibility and as a duty to their readers to adopt traditional journalistic practices such as attributing information and images to their sources, verifying if what is purported to be fact is that, identifying opinion (and opinion pieces are valid journalism) an such and the other practices that have proven of value. On social media, especially, repostings often strip images of their sources, however there are now online tools to trace them back to where they came from. I suggest it good social media practice to credit a photographer, illustrator or writer as this is plain honesty and a good, moral thing to do.

Testimony to the dominance of the visual

Carlos Miller’s book is a testament to the dominance of the visual in contemporary media. And it’s not only online media — print magazines have gone increasingly visual with large photographs being featured. Surfing magazines were early adopters of photographic communication with their sometimes A4 page size images (no, it is not true that this implies that surfers lack basic literacy and reading skills) and they have been followed by other topic-based publications.

The web, especially, has reinforced the role of visual communication. For citizen journalists this makes a basic photographic ability valuable, as does investing in a reasonable quality point-and-shoot camera and a smartphone with a good camera built in. Learning to use photo processing software like Snapseed to improve photos is also a valuable skill. The processing software that comes built-in to phone cameras like recent iPhones (and, presumably, Android devices) do a good job but are nowhere near as versatile as Snapseed and similar software.

Unlike the days when we needed a darkroom with all its kit, or when we paid for our film to be processed and had to wait for that to be done, we can now shoot, process, write accompanying text and post online while in the field. For an increasing number of photojournalists, the camera, an iPad and a broadband link make up their publishing platform. If you report on Instagram or a similar service then your smartphone becomes your camera, processing and publishing device. And if your link your social media to Twitter then you reach even more people, if that is what you want to do. In field processing and media production like this, the coffee bar becomes the office.

That smartphone camera is the one that is always with you when something interesting happens. Gaining basic proficiency in it’s capabilities for still and video imaging, and for audio recording for interviews and audio actuality, and learning to use a capable photo processing app to sharpen, colour balance and add a little contrast to your images is all you need.

This is the advantage Carlos points to in his book. It’s a book for our times and one that highlights the rise of a new type of journalism, a DIY journalism and one that through respected and authoritative bloggers is seen by an increasing number as more democratic and more trustworthy than the editorial monocultures of corporate newspapers and TV.

Read The Citizen Journalist and make real the slogan in the 1969 movie, Medium Cool: The whole world is watching (repeat).

- The Citizen Journalist. Carlos Miller, 2014. Ilex, UK. Softcover. My copy from Kinokuniya books, Sydney. $24.95.

- Photography Is Not A Crime: http://photographyisnotacrime.com

Related stories on photoghraphy:

How Photography Saved the Wilderness

Enforcing accountability with cameras