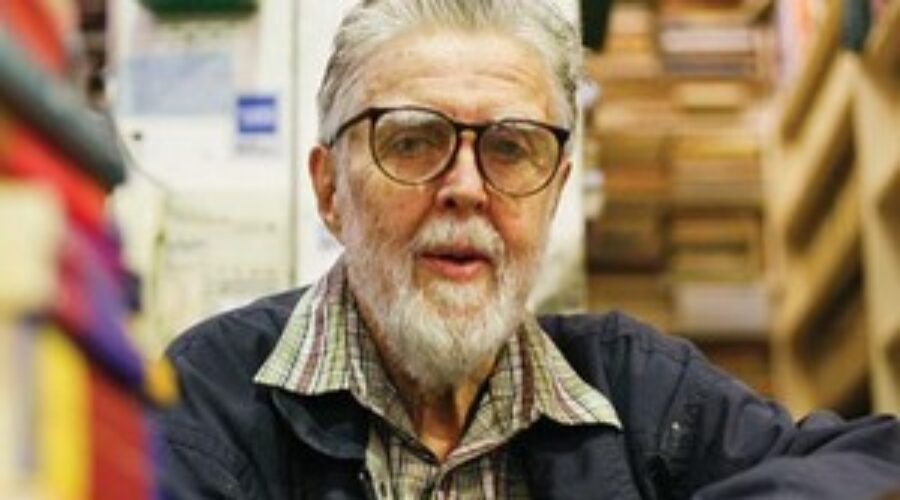

Farewell, Bob, and thanks for a life that touched so many

[three_fifth_last][/three_fifth_last]THE MELLOW, MELONCHOLY SOUND of a sax drifted over the Sussex-Goulburn intersection that afternoon. La Vie en Rose, the song popularized by Edith Piaf, was a fitting sound this fine but cold, late Autumn day in the city and it suited my mood as I looked past the player, down the road to a Korean restaurant that wasn’t there forty years ago.

What was there at that time, just down the road in the old, two storey building occupied by the restaurant, was one of those individuals who, through their force of personality and ideas make a distinct mark on the city and the society they inhabit. The mark these few make can be elegant or it can be blunt. It can be subtle or it can be loud.

Bob Gould’s mark was certainly not elegant. It was blunt and loud yet in it’s loudness it was considered and well argued.

…he suggested I come down to this Third World Bookshop in Goulburn Street on Saturday…

I encountered Bob as the Autumn of 1967 became the Winter when I stumbled upon an old school friend. That my encounter happened in that year, at the birth of what became the youthful counterculture, I like to think is significant. My friend and I had been at Brisbane State High together and unbeknown to each other—we lost contact after our school years—we had made our separate ways to the big city—Sydney. Certainly bigger, more worldly and more dynamic than Brisbane during those years, that’s for sure.

My school friend, Keith James, had acquired the accoutrements of 1960s youth—long hair and beard—and I failed to recognised him at first. But he suggested I come down to this Third World Bookshop in Goulburn Street on Saturday for the parties and folk music that was regular weekend fair.

Keith worked there and was to be found in the record shop of number 35. That was all there was initially, the annexation of number 37 Goulburn Street came later. There, over that summer of 67/68, I became acquainted with the music the shop stocked—Janis Joplin and the Holding Company, Surrealistic Pillow, The Doors, Country Joe and the Fish and all the rest of that cultural pantheon. What an odd fit with the heavy, hardback Marxist tomes displayed above, I thought. It was juxtaposition that epitomised the Third World Bookshop and the social movement that was to grow within it. And presiding over it all was Bob Gould and his accomplices, the Percy brothers.

That’s how I got to meet this Bob Gould character. He was usually ensconced behind the bookshop counter or was to be found in animated discussion on political points that were beyond my limited life experience.

…As noteriety made the bookshop better known, more and more young people were attracted to it and these Bob would engage in conversation…

I got the impression that Bob was a little critical of the youthful counterculture then taking shape, yet he accepted us and tried to put our heads straight… well, as he saw straight anyhow. I remember him as argumentative, mentally formidable, sometimes boisterous and exuberant, loud and a force in the world in the way that a strong seasonal wind is a force… always present and always blowing a gale against the pillars of the establishment.

Bob’s traditional Marxism was not something that most of this youthful cohort would identify with. Their politics was bound up with the youth chinese culture in a blend of lifestyle, personal expression, music and exuberance in what became known as the New Left. It coexisted uneasily with the old Marxist left but both shared an opposition to the war in Vietnam. That was the glue that bound them in uneasy alliance and that held together the diverse social assemblage around the Third World Bookshop.

As noteriety made the bookshop better known, more and more young people were attracted to it and these Bob would engage in conversation. Yet, like everything Bob did, there was reason behind his questions about who they were and where they came from. It was as if he was doing some kind of survey of the demographic that was attracted to the bookshop. Once, he remarked that it was the brightest of those middle class kids who were attracted to the place and the youth movement it housed.

If there was one thing that stood out in Bob’s character, apart, that is, from his alert intelligence and his articulateness, it was courage. Why courage? Because that’s what it took to stand up and oppose the establishment, whether that establishment was the government of the day or the establishment of the old left wrapped in its own version of conservatism. Bob’s courage was also evident in opposing a war that, in the mid-sixties, was largely unknown to the Australian public.

In his own way Bob was a Cold War warrior, but with a difference. He was not afraid to turn his critical gaze on the Soviet Union as much as he would turn it on the Western powers. By the time the Third World Bookshop and the youth group, Resistance, made its appearance, Bob had already raised ire of old left conservatives by opposing the Soviet invasion of Hungary. Later, he did a rerun of that by opposing the Soviet intervention in Czechoslovakia, making the link between that invasion and the war in Vietnam and painting the inhabitants of the Kremlin and the White House with the same critical brush.

His was a Marxism with a more independent streak that was based in the history of Australia’s own lobor movement. Added to this melange of Gouldian politics was the politics of his predecessors… when it wasn’t Vietnam that was his focus it was Irish republicianism.

It’s probably trite to say that Bob was a product of his time, but it was those times that formed him and in whose waters he so ably swam. It was on the outgoing tide of those waters that some of us encountered him as the late sixties gave was to the seventies. While it was Bob the political creature that some encountered, it was Bob the bookshop proprieter that othes found him as, and again it was his formidable force of character that carried him through this phase of his life.

In this role, he built a commercial mini-empire on publishers remainders and the notereity and experience that he gained through the Third World Bookshop on its varied journey over the years from Goulburn Street to George Street to Leichhardt to King Street, Newtown. Then there’s the shorter-lived bookshops in Melbourne and Adelaide of the late sixties and early seventies I think the Adelaide shop lasted into.

…a surruptitious, behind-the-counter sale of books banned by the state government…

Any remembrance of Bob must recognise that the bookshop, in its successive Goulburn Street venues of number 35-37, then its move across the road to larger premises at number 20a, was the platform for assaults on NSW’s censorship laws. Socially, the laws became increasingly untenable as the sixties gave way to the seventies with that decade’s freer social attitudes.

There, in 20a, along with the newspapers of the US underground press, as it was known (wasn’t one called the Berkeley Barb?), the Personality Posters and the rest of the stuff was a surruptitious, behind-the-counter sale of books banned by the state government. Occasionally, when they belatedly got wind of Bob’s audacity at disobeying unpopular laws, the police would stage a raid to seize the offending titles. Somehow, the media would have been tipped off about the impending raid and would be there, waiting at the bookshop. Needless to say, the police would usually leave with only a few of the offending books and, after they left, trade in banned books would resume.

…Bob accepted those middle class kids of the late sixties into the social melange that was the Third World Bookshop…

So, Bob Gould—leftist with independent line, bookseller, political intellectual, labour movement champion and influencer of the numerous people who encountered him. He leaves a legacy of daring, appropriate to his role as a change agent. But as I say farewell to Bob with these inadequate words, I ask myself what lessons his life, in the period that I encountered him, leave for me. These I sum up as the value of courage, the value of questioning everything irrespective of source, the value of applied intelligence and the value of acceptance of people different to yourself, just as Bob accepted those middle class kids of the late sixties into the social melange that was the Third World Bookshop.

Edith Piaf’s song, coming from the mouth of that sax that cold Sydney afternoon, is a sentimental piece. As it rose over the Sussex-Goulburn intersection I turned, hands in pockets against the chilly wind, and walked on, feeling a little sentimental myself about that old building just down the street. It occurred to me that the passing of the man who once inhabited the place, whose voice and laughter would rise above all others, whose cutting intelligence was so formidable, marked the ending of a seldom acknowledged and very occasional presence in my own life.

Writing these words, those of Joan Baez come to mind, and although they are about another significant figure from the collective past shared by some of us, I think they describe Bob’s entry as an influence in our own lives:

“…You’re a savage gift on a wayward bus

But you stepped down and you sang to us…”

(Winds of the Old Days, Joan Baez).

Thanks, Bob Gould, and farewell. Your life touched ours in so many ways.