A literature of past possibilites

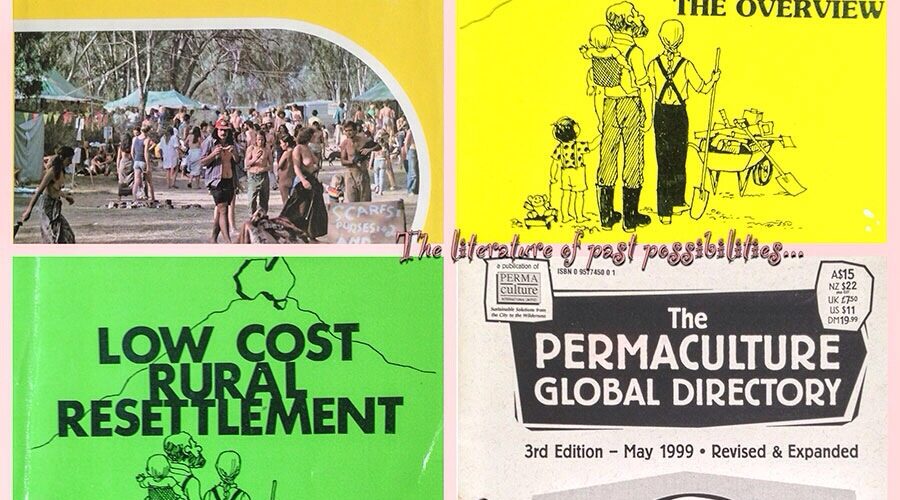

THE BOOKS YOU SEE in the composite illustration accompanying this story link past and present. They link what was a pioneering social experiment with its refined, socially safer version developed initially by permaculture people.

I’m talking about people leaving the cities for a rural life. It’s been a feature of permaculture over its more-than 35 year history and it’s been a theme in many a permaculture design course. Yet, it’s a theme with limitations posed by the availability of work in rural areas.

That was less a problem for those who made the rural move in the 1970s as rural economies were more bouyant then — there were jobs that you could find. It is far more of a problem now, with many rural economies in decline. As someone moving into a rural permaculture hamlet told me, the ecovillage lifestyle suits those who work independently from home and those few who have skills in demand locally, but it’s more of a problem for everyone else.

The landscape design focus of most permaculture courses has traditionally been on the rural smallholding, though possibly less so now than in the past. But there’s something contradictory here and it is this: the rural smallholding as a farming livelihood is not only hard work, it’s difficult to make financially viable. It’s no secret that a great many Australian farms are financially supported by a family member working off-farm in the nearest town. Small scale farming also holds little attraction to today’s youth, and that’s a challenge for Australia’s farming future.

For the more adventurous among the youth of the 1970s the attraction of the rural smallholding or larger scale farm wasn’t so much about farming, it was about shared living.

THE PAST REVIVED

To look to the rural smallholding as a permaculture design course focus is to look to the past. The past, you ask? Yes, it is reminiscent of the great exodus of youth from the cities to intentional communities, rural towns and farmland through the 1970s. This involved tens of thousands of young people.

In the 1980s it received attention from government which began to explore the potential for rural living and what was called ‘alternative lifestyles’ as an option for young people. There were meetings between those pioneering the new rural lifestyle and the NSW government, and a committee was formed to discuss the idea. I recall Dudley Leggett coming down to Sydney from Northern NSW for meetings of that committee.

Universities became involved. One of the books whose cover appears in the photo composite accompanying this story — Alternative Australia — was published in 1979 and was written by researcher, Peter Cock. It analysed what had by then grown into a social movement the likes and scale of which we have never seen before or since. It offers a valuable sociological description of the movement and its time.

There was no accurate count of the number participating in this new lifestyle as figures (see later) by Bill Metcalfe, an academic who researched the topic and produced a number of books on intentional community living, and a book from the University of New England, indicate.

The other two covers in the composite — Low Cost Rural Resettlement and Sustainable Rural Resettlement — were published in 1983 and 1984 respectively. They were the product of the Australian Rural Adjustment Unit of the University of New England at Armidale, set up to investigate ways to reduce conflict between local government and what it termed ‘homesteaders’ after the Hawke federal Labor government showed interest in alternative lifestyles.

The first book took those seeking low cost rural living through the local government planning process, a place where confusion and disagreement was rampant. The second looked at ways government could facilitate the lifestyle.

That second volume explains its rationale in its overview. Putting university estimates of the number of people participating in what the author terms alternative lifestyles at around 60,000 (an estimate by academic, Bill Metcalf), the overview goes on:

“A substantial portion of these people are living illegally and the reason for this lies squarely at the doorstep of the three tiers of government… homesteaders are people who presently aspire to SRR (Sustainable Rural Resettlement)… (they) are scattered throughout Australia and many of the estimated 160,000 such people wish to live a ‘commune’ lifestyle.”

Interest by government and academia and the number of books on the topic (there were a couple in addition to those mentioned above), mainly by university researchers, demonstrates how seriously rural resettlement and intentional communities were taken at the time.

The other book in the composite, the Permaculture Global Directory, came much later, a product of the 1990s if my memory serves me well. It was an attempt by Permaculture International Ltd (now Permaculture Australia http://permacultureaustralia.org.au/) to encapsulate the spread of the permaculture design system worldwide. I wouldn’t like to attempt to compile a similar list today as the movement has diversified and, with permaculture-trained people working in other organisations, just what constitutes a bona fide permaculture organisation or even the practice of permaculture is an open question.

What’s not in the composite is the well-used and influential 1970s book, Low Cost Country Home Building. It’s missing because my copy disappeared decades ago. The book, which was about construction, became something of a DIY manual for the builders of those early intentional communities and others of the time who set forth by themselves to construct their dream life in the rural backblocks.

• Find the book: http://trove.nla.gov.au/work/25427835?selectedversion=NBD2103762

• Learn about the author: http://www.smh.com.au/comment/obituaries/giant-architect-built-for-justice-20130222-2ewqq.html

WHAT CAN WE LEARN?

What’s the learning for us, now, from the social movement described in these books?

First is that permaculture cannot be extracted as some stand-alone idea from the cultural matrix of the time of its origin. That origin matrix is alternative culture — not exclusively, but substantially.

The link is something that some in permaculture have in the past denied and decried, describing it as permaculture’s ‘hippy past’. Many of those who said this were not born when hippies roamed the landscape and were reacting to mainstream media stereotypes. At the time, there was no clear distinction made between hippy and alternative and I think it’s accurate to describe them as locations on a continuum, with ‘indolent hippies’ at one end and innovative, creative alternatives at the other (sweeping generalisation, I know; apologies to any hippies still out there).

The second learning is that the intentional communities of the 1970s morphed into the familiar ecovillages of today. As one of the developers of the first ecovillage, Crystal Waters Permaculture Village said, they looked at the past, learned from it and built something better. This is an evolutionary development and today ecovillages are home to middle class people who can make a living in rural areas.

History repeats but never on the same track. Permaculture people, today, come up with ideas they believe to be new but which those with long memories will recognise in a similar form from way back. Sometimes, that past is forgotten, an example, by way of analogy, being Michael Mobbs’ sustainable house in Chippendale, Sydney. Michael’s is credited with being the first intentionally sustainable house in Australia, yet it stands less than 300 metres from where the actual first sustainable house stood.

That first sustainable house was only a temporary structure, a design-and-build exercise by Sydney University architecture students of the 1970s. Out of that course came earth building architects, Brian Woodward and Rye Mitchell. Brian became known to the Sydney permaculture community of a couple decades ago for the earth building courses at his Wollombi property, Earthways. In the 1980s, Rye and a group would meet at the Permaculture Epicentre on Enmore Road, now the premises of Sydney’s longest running food co-op, Alfalfa House. There, they were planning an earth-built intentional community on the NSW south coast, modelled on the traditional Italian hill village as a close-packed settlement surrounded by open space and agricultural land. I was one of that group.

Another learning from the not-all-that-distant-past is that government could have a role in enabling sustainable rural resettlement, however the prospects for this appear dim, going by the types of government and politician, of all parties, that we have been afflicted with since the 1990s. Rural resettlment simply doesn’t fit their economic models.

We can trace the origin of community living and, to a large extent, of permaculture itself to the cultural melange that was the 1970s youth culture, however the concept that permaculture encapsulates actually preceded it by decades. It was the idea of polymath, Buckminster Fuller, and it was known as ‘whole systems design’. Perhaps it’s no accident that Fuller was a profound influence on the alternative culture of the 1970s.

What would be both truly constructive and instructive would be to define what all the useful stuff from the seventies and eighties is, and which of it is worth reinventing in modern form.