THE STRUCTURE OF PERMACULTURE — understanding the network

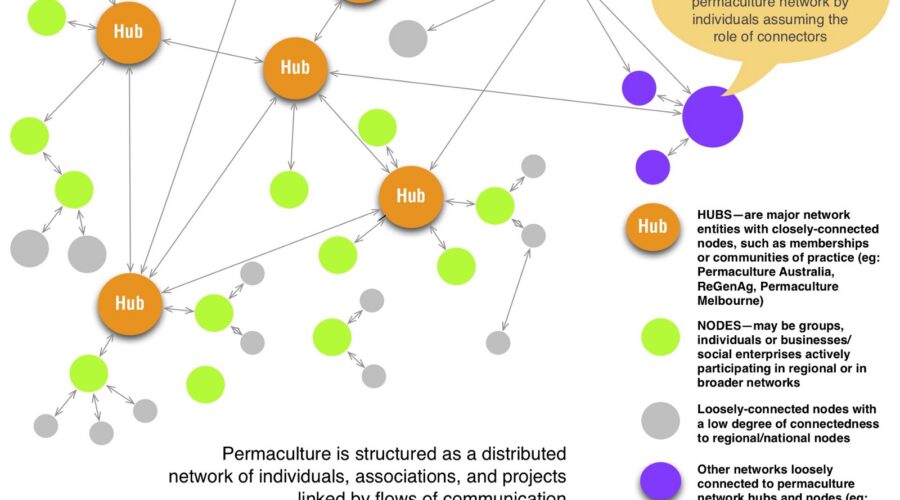

- Permaculture in Australia is structured as a distributed network

- the network consists of nodes and hubs and the connections between them

- some nodes attract other nodes to become hubs; through preferential attachment, well-populated hubs continue to attract nodes and become larger and more influential

- hubs focused on some particular aspect of permaculture such as education, landscape design, permaculture in schools, regenerative farming or home gardening form components of interest within the broader distributed network of permaculture

- connectors link nodes and hubs and transfer information between them.

WHAT do the human brain, railway and highway systems, friendships, professional and social associations, the internet, trading systems and ecological systems have in common?

Here’s what: they are systems. They are complex wholes made up of integrated, interacting parts that produce a combined effect that is greater than the simple sum of their parts. And there is something more those things all have in common: they are made up of networks.

Networks are a pattern in nature. Think of food webs which link soil life > plant > herbivores > omnivores > carnivores into a network of feeding relationships whose effect, which is greater than the simple sum of its parts, is functioning ecosystems. There’s more to ecological systems than that, but when we think ecosystem we think of relationships combined into networks.

Permaculture design system practitioners say their system mimics nature, that it is nature-led design. What they mean is they apply what they see in nature to the design of farms and gardens, villages and to other applications. Think of it as applied systems thinking. This has been the approach ever since Bill Mollison and David Holmgren launched the permaculture design system in a book called Permaculture One in 1978, forty years ago.

The network is a pattern in nature

We know that the network is a basic pattern in nature as well as in human systems. The network is also a pattern that gives overall structure to the permaculture design system. It is the pattern that has evolved at the regional, national and global scales.

Nobody designed and constructed permaculture this way. The network structure self-organised as permaculture practitioners set up local, then national permaculture organisations and as individual practitioners sought connection and communication with other practitioners. Permaculture self-structured as a distributed network both nationally and globally. It is a distributed network because its nodes are geographically dispersed across the country, across the world. It has no head office, no central authority.

When Bill Mollison started teaching permaculture at his Stanley, Tasmania, home base in the early 1980s, his students went home and set up local permaculture associations. Along with Stanley, those locations formed the first nodes of what would become a network of permaculture nodes, usually structured as associations and sometimes remaining as single individuals, in city and country. To continue their development, those nodes needed to communicate to recruit new participants, to share what they learned, pass on news and start building the knowledge of how to do permaculture.

This was before the internet. News of permaculture was spread through word-of-mouth and in the pages of a print magazine, Permaculture. Started in 1978 by Terry White in Maryborough, Victoria, the magazine provided the connection between the emerging regional nodes. It became the enabler of the permaculture network, the connection through which word spread. Soon, new nodes emerged in city and country and, linked by Permaculture magazine, a network of distributed nodes started to form. As the means of communication that connected the nodes, Permaculture magazine (it later became Permaculture International Journal) demonstrated the prime importance of communication and media in establishing networks.

Nodes connect and become hubs

Today, permaculture in Australia is made up of geographically scattered nodes built around permaculture community associations, educators, businesses and individuals. Connecting them are flows of information. This is the distributed network and it is given coherence by permaculture’s code of ethics, a set of design principles and by a sense of belonging among permaculture practitioners.

As a distributed network permaculture has no head office, no headquarters, no central node through which information flows. Nodes are independent of each other and are connected only by flows of information and sometimes by social exchange including the physical connection that occurs at the biennial permaculture convergences.

In Australia, Permaculture Victoria, Permaculture Sydney West, Permaculture Sydney North and the Permaculture Research Institute serve as examples of long-lived permaculture association that form influential nodes that have their own smaller networks. Others nodes are shorter-lived. When they go inactive or disappear, communication reroutes into different channels through the greater permaculture network. This makes the network resilient when faced with change.

Hubs gain influence as they grow

Nodes become numerically stronger by engaging in activities that bring in greater numbers of people, sometimes from places distant to where they operate. They make connections with compatible organisations and individuals within their region. Soon, they start to develop their own regional networks and, in doing so, become hubs.

Hubs emerge from homophily, the social clustering by which the like-minded get together in person or online. At its best, homophily brings advantages like mutual learning and benefit, and friendship. In its worst case homophily leads to closed and defensive mindsets, especially where participants in homophilous hubs resist new ideas coming in from outside, and especially where those ideas challenge what hub participants believe. The result is the ‘echo chamber effect’ in which hub participants bounce the same messages and ideas back and forth to and from each other. The effect is to reinforce ideas acceptable to those in the echo chamber and to resist and exclude those that aren’t. The outcome can be the fragmentation of a social movement into factions.

In the 1990s and into the new century, Permaculture Sydney North demonstrated how a regional permaculture association could grow into a hub with metropolitan, even national reach and influence. With other permaculture associations in the city having faded, people from suburbs distant from Sydney’s North Shore joined and participated in the organisation. It’s attraction grew and soon it became a large and influential regional association with many connections. It grew from a node into a hub within the national permaculture network as its influence extended far beyond its region. This is how hubs come to gain an influence well beyond their region and their membership numbers. Leadership of hubs can bring national recognition to individuals and, often, a reputation as a mover and shaker.

How nodes grow into hubs

As hubs grow from smaller, lesser-connected nodes they demonstrate the phenomenon of ‘preferential attachment’. That is, as they grow they become more prominent and attract an increasing number of connections. That is how hubs with the most connections attract even more and continue to grow both in numbers and influence.

…the value of a network is proportional to the number of connected nodes.

The principle of ‘early establishment’ plays a role here. The first, or the first few entities to establish, gain a starters’ advantage and attract an early and growing batch of followers. A familiar example comes from social media where Facebook became the first of its type. It grew rapidly until it dominated the social media space. Alternative services found it difficult to become established. As hubs grow they leave less space for new hubs of the type.

Hubs become dominant within a network because the great majority of nodes, the smaller entities on a network, have comparatively few connections. Hubs are nodes with a large number of connections to and from other nodes. In Australia, that includes the Permaculture Research Institute, Permaculture Victoria, the Milkwood permaculture network and Permaculture Australia.

Connections within hubs

Hubs are not all the same. The difference between hubs lies in their structure. When we look at smaller, regional hubs such as those covering a cluster of suburbs, a limited region of a city or a rural centre, we find a large number of people know each other although not everyone is known to all. To contact someone you do not personally know in the hub there is only a short number of hops between participants to find them. Hubs can be a small world to themselves, which is why they are known as ‘small world networks’. Individuals have their own circles of friends and acquaintances — their own social networks — so contacting people might take only a few intermediate connections between individuals to find them.

The same applies between nodes in a network. The ‘path length’ between nodes is a measure of the number of hops or connections information makes to get from one node to another. For example, if I want to contact permaculture co-inventor, David Holmgren, and I don’t have contact information for him but I know how to contact Richard Telford at Permaculture Principles, Richard could put me in contact with David because he is connected to him through the network in the region where both live. My path length to David is two — two hops to find him.

The number of connections does not necessarily imply a high degree of participation or practical activity by the connected nodes.

Stanley Milgram was an early experimenter in this phenomenon and found that around six hops could connect people not personally known to each other. This became the well known ‘six degrees of separation’, six being an approximate number.

The necessity of connectors

Irrespective of the degree of separation or the number of hops between individuals to find one with direct connection to whom you are looking to contact, critical to finding people are the ’connectors’. They are the people who have a high degree of connection to others and who can ease communication in a network. Sometimes called ‘networkers’, connectors are links within and between networks and are critical to their effective functioning. Connectors are especially important to information flow between ‘island hubs’, nodes and hubs that are not closely connected to larger state-based or national networks.

The Networking Principle states that the value of a network is proportional to the number of connected nodes and the degree of connection between them. The number of connections does not necessarily imply a high degree of participation or activity by the connected nodes. A hub with a large number of connections to inactive nodes could be less effective in developing or promoting permaculture or some other idea than a hub connected to a smaller number of active nodes. The flow of information creates opportunity but it doesn’t make those opportunities happen. That depends on initiative.

Hubs accrete into components

‘Components’ are clusters of hubs that aggregate around some specific applications of permaculture such as permaculture education, social permaculture, landuse design or home and community garden food production. Permaculture educators clustered around Permaculture Australia’s workplace training scheme, Accredited Permaculture Education, for example, form a component in permaculture education.

When more than half (the number is arbitrary) the nodes in a component connect to other related components, network theory says they form a unified ‘giant component’ within the greater network.

Permaculture educators linking within a region or a state form a distinct component. When they link to other components or clusters of permaculture educators in other states and regions they form a ‘giant component’. It’s a way of imagining how hubs scale-up.

Do the giant components of permaculture in Australia around education, farming systems, small scale home garden agriculture and homesteading, social permaculture and others fragment permaculture into small worlds built around special interests? This might be true in some instances, however it is offset by the loose sense of commonality and belonging that comes from a shared adherence to permaculture’s ethics and principles and by the important role of connectors in migrating information between them. Giant components can just as well be seen as evidence for the diversity of permaculture applications.

How power is gained in the permaculture network

Power or influence in permaculture in Australia stems from someone’s position and role in the larger distributed network.

There are two ways to achieve power, although perhaps we would better call it influence. One comes from being a first starter. David Holmgren has a low to non-existent profile on social media. He doesn’t post to the social media platform used by 95 percent of Australian social media users — Facebook — although Melliodora, his permaculture consultancy, has a page (https://www.facebook.com/MelliodoraHepburnPermaculture/) as well as a website (https://holmgren.com.au/melliodora/). David’s power in the network comes through his first starter role as co-inventor of the permaculture design system, his teaching permaculture, as author of several books on permaculture and by positioning himself as a public intellectual within the movement.

Milkwood Permaculture had to take the other route to influence, and create it. They did that when some years ago they launched a concentrated social media campaign to promote their courses. They quickly built an online presence that established their permaculture education business alongside established educators such as the Permaculture Institute and Permaculture College Australia.

Milkwood, Permaculture College Australia and the Permaculture Research Institute and others demonstrate how the ‘clustering coefficient’ clumps individuals and organisations into hubs. Through preferential attachment it attracts an increasing number of links creating, in effect, a small world network.

The network effect is critical to permaculture as a social movement

Permaculture evolved into a distributed network because it had no head office, no central direction.

In its early period the Permaculture Institute in Tasmania was the recognised focal point for the design system because its co-inventor, Bill Mollison, lived and taught there. The Institute had the first starter advantage and through those early decades wielded its influence until new educators in different places started to build their own small world networks.

Permaculture diversified and the early influential role of the Institute declined. Although the idea of franchising permaculture design was mentioned in those early years, which could have centralised the design system, it evolved into a geographically decentralised practice as nodes and then regional hubs set up.

The Network Effect — value being proportional to the number of active participants in a network — supports permaculture’s value to its various components and binds it into a loose though more or less unitary social movement.