A distant voice calls from permaculture’s dawn time

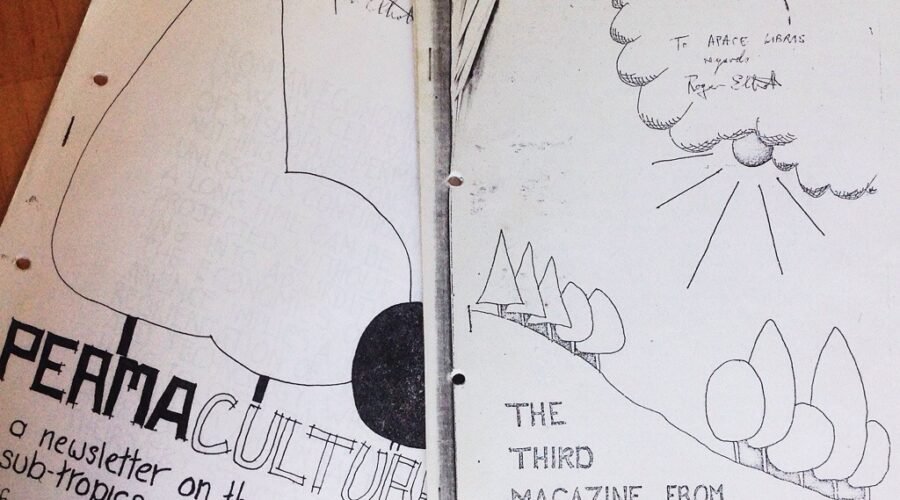

SOMETIMES, the best discoveries are made by accident. I was rummaging through the library of an international development organisation I was working for at the time — that time being the latter half of the 1990s — when I discovered them, a couple journals published by what must have been one of the very first permaculture associations to set up in Australia.

Carefully opening the aged, photocopied pages of the journals and reading a paragraph here and there, I realised that what I held in my hand was a record of a permaculture that might have been, a permaculture that didn’t eventuate. It was a description of how permaculture’s earliest of thinkers envisioned the spread of the design system, and it was information that had largely faded from the design system’s scanty memory.

I was unaware of South East Queensland Permaculture until I stumbled on those journals. How long they had rested unopened in that library? A period measured in decades, probably. Surely the of that primal permaculture organisation would long ago have scattered in the same way that many who attended to permaculture’s early years have been.

I was in for a surprise, however. When I wrote about those discovered journals in The Permaculture Papers a few years later, I received an email from someone who, somehow, had come across my writing. And that someone had been a member of South East Queensland Permaculture.

A DIFFERENT KIND OF PERMACULTURE

Permaculture — A newsletter on the subtropics starts by describing one of the earliest permaculture design courses. In doing so it highlights how crucial was Bill Mollison’s northern Tasmanian property on the Bass Strait coast to training the first of what became a small cadre of permaculture designers and educators. This was the start of permaculture’s educational lineages.

“Seventeen people from most corners of Australia gathered for a 2-week course in Permaculture Design at the Tagari Community in Stanley on the north-west coast of Tasmania. Bill Mollison lectured about the two Permaculture books and shared his experiences,” the journal reports.

“The course is coordinated by Earl Saxon who gave a generalised talk on ecological principles. Bill encouraged the participants to become expert in design but to link up with other people, eg. unemployed groups and trained implementers.”

An addendum speaks of the further spread of the design system: “One of the 1980 permaculture design workshops, lectured by Bill Mollison, was held in the Coolangatta region from 27th April to 3rd May, at Tomewin”.

ALTERNATIVES: THE EARLY LINKS

The story goes on to highlight permaculture’s early links and partial origin within what was called at the time the ‘alternative’ or ‘alternative lifestyles’ movement. This was a sizeable social movement in both city and country that was studied and documented by academic researchers like Peter Cock who wrote the substantial book, Alternative Australia. In rural areas, the movement pioneered the intentional communities, the early antecedents of today’s ecovillages, and in both city and country, and was inspired by the writings of Fritz Schumacher and Buckminster Fuller with his ‘whole systems design’. It tinkered with the first wave of what was then called ‘alternative technology’ but part of which today has been mainstreamed as renewable energy systems.

“The emphasis is on sharing with the existing alternative movement for labour and expertise. Paying jobs would come from governments, councils and other institutions and some private urban and farm properties.

“Design aims to maximise energy gains on site. Emphasis is on efficient use of all features (multiuse wherever possible). Design is suited to different needs.

“Costs vary depending on client abilities to pay — ‘cheap’ or ‘in kind’ for the alternative movement — normal landscape fees for institutions, etc, eg. $300 for average urban situations. The amount saved is far in excess of this even in the first few months of living on site.”

A DIFFERENT PROPAGATION

Then comes the vision of how permaculture would propagate through society.

“The agents trained in the course will be fully franchised when they submit ten designs for Tagari’s approval.”

This didn’t happen. To understand why requires us to look back into the design system and to realise that things often turn out differently to what their developers imagine.

At the time, and for a few years after the journal was published, there persisted the idea that it would be people with existing qualifications, such as landscape architects, planners, other design professionals and horticulturists who would add permaculture design to their professional offerings. Illustrating this was the three-day permaculture design course held at Glebe Town Hall in Sydney, organised by landscape architect and permaculture designer, Birgit Seidlich, and which was lectured in part by Bill Mollison and Geoff Young. Geoff later went on the join the start-up crew for Crystal Waters Permaculture Village in south east Queensland.

In the 1990s, Birgit Seidlich brought a professional design influence to permaculture in Sydney. She taught in the PacficEdge urban permaculture design course in Sydney and, while working for Leichhardt Council in Sydney’s Inner West, developed an early environment management plan. Birgit is responsible for the olive tree grove in Pioneer Park, Leichhardt, and early attempt at edible landscaping in public places.

What happened instead of it becoming a professional add-on was that permaculture attracted a different clientele and developed into a social movement rather than a professional practice. Perhaps Bill recognised this when, at age 50, he quit his University of Tasmania job lecturing in environmental psychology to go out and spread permaculture.

Permaculture — A newsletter on the subtropics goes on to identify some of those practical visionaries of permaculture’s dawn time who attended that course in northern Tasmania.

“Designers in Queensland from Brisbane River north are Max Lindegger and Bill Peak at Nambour and Cooroy. From Brisbane River south into NSW to the Bellingen River are John Palmer and Bob Roe from Tomewin and Uki”.

Of all those mentioned, the only one with current profile in permaculture is Max Lindegger. Max continues to teach permaculture at the rural community he was part of establishing — Crystal Waters. A resident of the village since its beginning, Max also works with the Global Ecovillage Movement. He attended the 2008 Australasian permaculture Convergence in Sydney, APC9.

South East Queensland Permaculture must have been a serious organisation. As well as publishing its journal, which appears to have been distributed shortly after 1980 at the same time that Terry White, in Maryborough, Victoria, was publishing Permaculture — the quarterly magazine that became the long-running Permaculture International Journal (it ceased publication in June 2000) — it set up a seed bank and seed exchange located in the Tweed region of Northern NSW. This might have been Australia’s first seed bank and seed saving program with a relationship to permaculture, and may well have existed around the time that Michel and Jude Fanton were developing ideas for the Seed Savers’ Network at their home at the Tuntable Falls intentional community.

LOST HISTORY TELLS A DIFFERENT STORY

The value of South East Queensland Permaculture’s journal lies in its shedding light on the design system’s very early days. In those times, the vision its few participants held for permaculture was to a large extent different to how it turned out.

Co-developer of the permaculture design system with Bill Mollison, David Holmgren, has spoken about how permaculture has lacked a sense of its own story and for many has been a design system without a history. All many students gain is a scanty version of the design system’s story from the point of view of their teachers, and what they learn is linked to the teacher’s educational lineage through the design system. This can make that story they get a partial one. Bill Mollison’s autobiography, Travels in Dreams, relieved this lack of a story for permaculture to some extent, something furthered by the later publication of Permaculture Pioneers.

By looking back at chance finds like Permaculture — A newsletter on the subtropics, a find that I made that day in that NGO library in Sydney, those of us involved in permaculture design and education can gain a view of the design system we are part of that is different to what is commonly held.